Russia lawmaker moves to close gay marriage loophole

Transgender woman married her girlfriend last week

darrenw

www.gaystarnews.com/article/russia-lawmaker-moves-close-gay-marriage-loophole141114

Russia lawmaker moves to close gay marriage loophole

Transgender woman married her girlfriend last week

darrenw

www.gaystarnews.com/article/russia-lawmaker-moves-close-gay-marriage-loophole141114

LGBT Awareness PKG

LGBT Awareness at The University of Georgia Does UGA offer a safe space for the LGBT community? How the LGBT Resource Center helps UGA students during their collegiate careers. Reporter:…

Malaysia bank denies promoting gay practices

Muslim group calls for a boycott of AmBank over its ties with a gay-friendly US bank

darrenw

www.gaystarnews.com/article/malaysia-bank-denies-promoting-gay-practices141114

Hong Kong’s Rainbow Parade Raises Awareness of LGBT Rights

Assignment 2: Dope Sheet Headline: Hong Kong’s Rainbow Parade Raises Awareness of LGBT Rights Description: The Annual Hong Kong Gay Pride Celebration has for many years, been a platform…

www.youtube.com/watch?v=2NKJf4Xi7fI&feature=youtube_gdata

The Power of a Complex Heritage

Diriye Osman is photographed by Bahareh Hosseini

When I first moved to London in my teens, people often asked me where I was from. For some reason this seemingly innocuous question yielded up some unwieldy responses on my part. I would reply that I was born in Somalia, grew up in Kenya and now called London home. It felt like a tediously lengthy statement every time the words tumbled out of my mouth.

One of the great markers of maturity is an appreciation for complexity. Although I’m of Somali descent, I did most of my growing up in Nairobi and London. As the years zipped by, the lens of my identity also zoomed out to encompass my sexuality as an out and proud gay man.

As a young gay African, I have been conditioned from an early age to consider my sexuality a dangerous deviation from my true heritage as a Somali by close kin and friends. As a young gay African coming of age in London, there was another whiplash of cultural confusion that one had to recover from again and again: that accepting your sexual identity doesn’t necessarily mean that the wider LGBT community, with its own preconceived notions of what constitutes a “valid” queer identity, will embrace you any more welcomingly than your own prejudiced kinsfolk do.

So what to do? There are only two options when one is barricaded in by banal yet dangerous stereotypes: Either shed some of the complex layers that have made you who you are or cling to those complexities and appreciate the value of the long game, the fact that there is power and strength in multiplicity, the fact that there is power and strength in a beautifully unwieldy heritage.

This is what I learned when I started writing Fairytales for Lost Children. The book, which focuses on the lives of young LGBT Somalis, made me realize that it was possible not only to respect cultural complexity but to revel in it. Ultimately, we are the only people who can give ourselves permission to live.

This message of hope is the connective thread between me and my readers. We may come from different parts of the world and have contradistinctive histories, but we all yearn for love, a modicum of peace, understanding and acceptance. Whether we voice it as such, we’re all looking for mirrors that reflect our realities back at us. We are all in pursuit of freedom regardless of where we are coming from. There is something deeply moving about this idea of interconnectedness, the notion that our individual complexities endow us with a sense of shared humanity.

When I first started writing, my younger brother, who was then in his pre-teens, complained to me that my characters all had Somali names, unlike the English characters he was so accustomed to reading about. I told him that it was important for me to write about Somali characters, that it was important that we all told our own stories and shared our heritage with the wider world. Initially he seemed unconvinced, but before long he too started writing stories that featured Somali characters.

That memory alone makes me happy to this day.

Diriye Osman is the Polari Prize-winning author of Fairytales for Lost Children (Team Angelica), a collection of acclaimed short stories about the LGBT Somali experience. You can purchase Fairytales for Lost Children here. You can connect with Diriye Osman via Tumblr.

Robbie Rogers gets multi-year contact extension with Los Angeles Galaxy

He remains the first and only openly gay player in Major League Soccer league

gregh

www.gaystarnews.com/article/robbie-rogers-gets-multi-year-contact-extension-los-angeles-galaxy141114

“A huge untapped market ” Milwaukee plays host to first LGBT Wedding Expo

MILWAUKEE (WITI) — It’s a historic wedding expo because of the couples it’s targeting. 54 vendors took part in the LGBT Wedding Expo, held Thursday, November 13th at the Radisson Milwaukee…

www.youtube.com/watch?v=DsESkFDGorU&feature=youtube_gdata

Ark. Church Gets Threatening Note in Response to Marriage Equality Support

After a Unitarian Universalist minister wrote a pro-LGBT letter to the editor of an area newspaper, her church got an anonymous homophobic note.

Stevie St. John

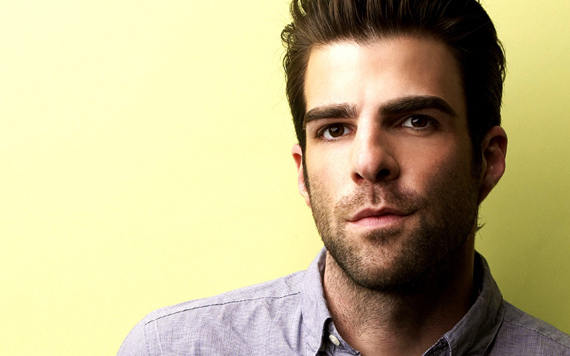

Stop Picking On Zachary Quinto

You can count on one hand the number of times a young, openly gay Hollywood actor has talked about HIV/AIDS in the last decade. In fact, you’d probably only need a couple of fingers. Zachary Quinto just boldly went where few gay thirty-somethings have gone before, talking passionately about how HIV is affecting his community, and he’s getting dumped on for straying from the HIV/AIDS party line. I want to thank him for being one of the few that gives a shit, and for speaking out about gay men and HIV.

For the record, I’m a fan. Heck, I’m practically a Quinto stalker. Being a dedicated Trekker since the series started reruns in 1969, I’ve been under his sway since his first uttered “live long, and prosper.” I admired his acting chops on stage in The Glass Menagerie, and froze up when he walked right past me at Anderson Cooper’s 46th birthday party. So yeah, stop picking on my Zachary!

But seriously, here’s what Mr. Quinto said to OUT Magazine that’s raised hackles:

“I think there’s a tremendous sense of complacency in the LGBT community,” Quinto says, citing the rising number of HIV infections in adolescents. “AIDS has lost the edge of horror it possessed when it swept through the world in the ’80s. Today’s generation sees it more as something to live with and something to be much less fearful of. And that comes with a sense of, dare I say, laziness.”

Quinto is similarly candid on prophylactic drugs, like PrEP, which many gay people have embraced as a long-awaited panacea. “We need to be really vigilant and open about the fact that these drugs are not to be taken to increase our ability to have recreational sex,” he says. “There’s an incredible underlying irresponsibility to that way of thinking…and we don’t yet know enough about this vein of medication to see where it’ll take us down the line.”

Sure, there’s some unhelpful finger-wagging here that won’t win Quinto any brownie points with many young gay men, but can anyone deny that complacency is now a major driver of new HIV infections in this group? Most of us have learned the hard way that using the plague years to browbeat younger generations doesn’t work, but hearing a 37-year-old reference those times should count for something. Quinto has learned his history, with evident respect, which puts him light-years ahead of most gay men his age.

His PrEP comments created the most stink. One wishes he hadn’t ditched Spock’s logic and love of science when discussing one of the most promising advances in the fight against HIV in years. But again, I’m amazed he mentioned it at all. According to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey, only 26 percent of gay or bisexual men have even heard that there’s a drug that prevents HIV infections.

Let’s use this as a teachable moment. I’d love to introduce Quinto to many of the early adopters of PrEP. Most of them are wise beyond their years, and have spent more time than most thinking about their own health and the health of their community. They are the epitome of gay male responsibility.

What do you say, Zack? Let’s talk.

You must be 18 years old or older to chat