How Do You Build A Gay Art Museum? Hunter O'Hanian On The History Of Leslie-Lohman

On Huff Post Arts&Culture, we spend a lot of time spotlighting amazing artists — new and old. Every once in a while, we like to profile a museum or institution doing good in the art world. This is one of them.

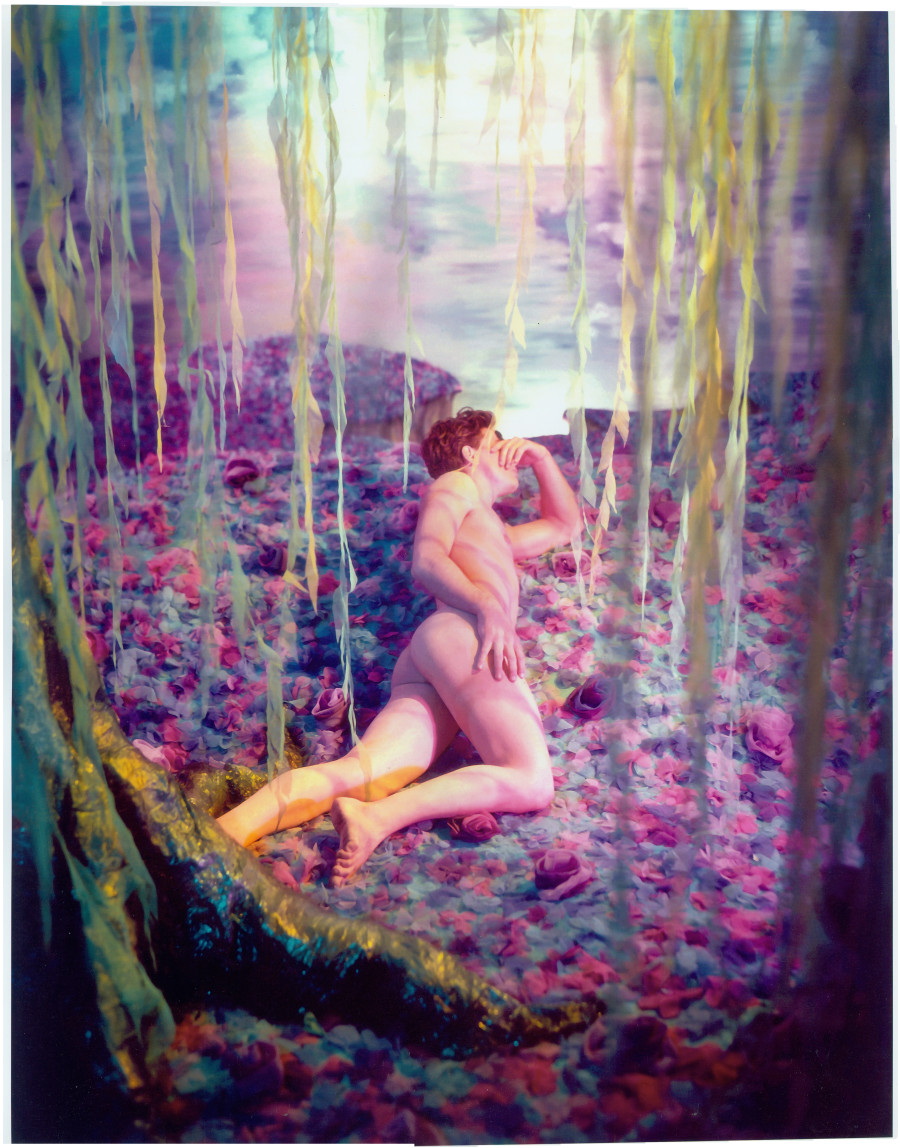

James Bidgood, Willow Tree (Bruce Kirkman), mid-1960s, Digital C-print, 19.688 x 15.438 in. Foundation Purchase.

“We have so many histories,” Hunter O’Hanian explained to me in a recent chat. I had asked him to give me the abridged history of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, the institution for which he currently serves as director. Indeed, the museum cites more than a few birthdays on its website — one in 1969, when Charles Leslie and the late Fritz Lohman opened their home to art enthusiasts, one in 1987, and another in 2011. O’Hanian clarified:

“We officially started in 1987, when people were dying of AIDS. Families would come in and throw everything away — throw away the gay art. It was obviously a terrible time, the ’80s in New York City. So Charles and Fritz, who lived in SoHo, decided that they wanted to do something about it.” The co-founders were already a large part of gay culture, O’Hanian explained, having welcomed 200 people to their first exhibition years before. Realizing that the art created by their friends and peers was being disposed of at a rapid pace, the two decided to set up a non-profit corporation to preserve and exhibit the works of art that spoke to the gay and lesbian community.

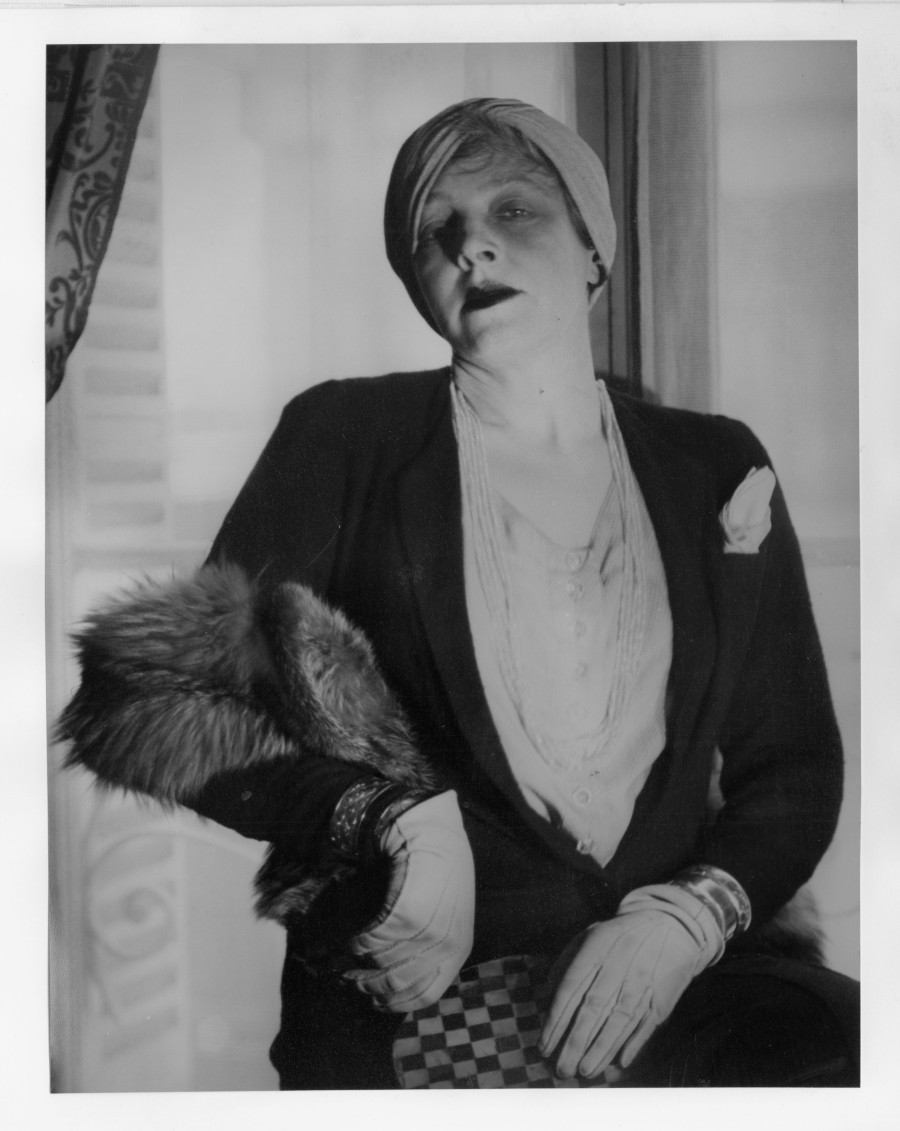

Peter Hujar, Ethyl Eichelberger as Auntie Belle Emme, 1979, Vintage gelatin silver print, 14.563 x 14.625 in. Gift of the Peter Hujar Archives.

Of course, 25 years ago, the road to setting up a non-profit dedicated to archiving gay history was a bumpy one. It took three years to get their tax exemption. The IRS was not happy about the word “gay” in the title, and it wasn’t until 1990 that the organization’s lawyers won their battle. Happily nestled at 127 Prince Street, the Leslie/Lohman Gay Art Foundation, Inc. functioned as a safe haven for work that was otherwise going to be destroyed. Those works piled in. By the time the organization transitioned to the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in 2011, it had collected over 24,000 pieces.

“From 1990 to 2010, over the course of 20 years, [Leslie and Lohman] did exhibitions, supported gay artists, and showed work that other galleries wouldn’t necessarily show. Some of it was erotic, some intuitive.” They added board members, moved to a 1,800-square-foot exhibition space, began acquiring new artworks and hired O’Hanian in 2012. With a provisional charter — the organization is set to achieve official museum status in 2016 — Leslie and Lohman’s legacy began mounting six to eight shows a year. This year the museum is expecting 30,000 visitors.

Alexander Kargaltsev, Black and White, 2014, Archival digital C-Print print, 19.938 x 29.938 in. Gift of the artist.

The museum now runs under a guest curator model. Individuals submit proposals for exhibitions to the museum’s committee, and O’Hanian guides the chosen submissions to fruition. At first, this made sense for the budget, but it also gives the museum an edge on perspectives. “We weren’t quite ready to have a single voice, so we have multiple voices.”

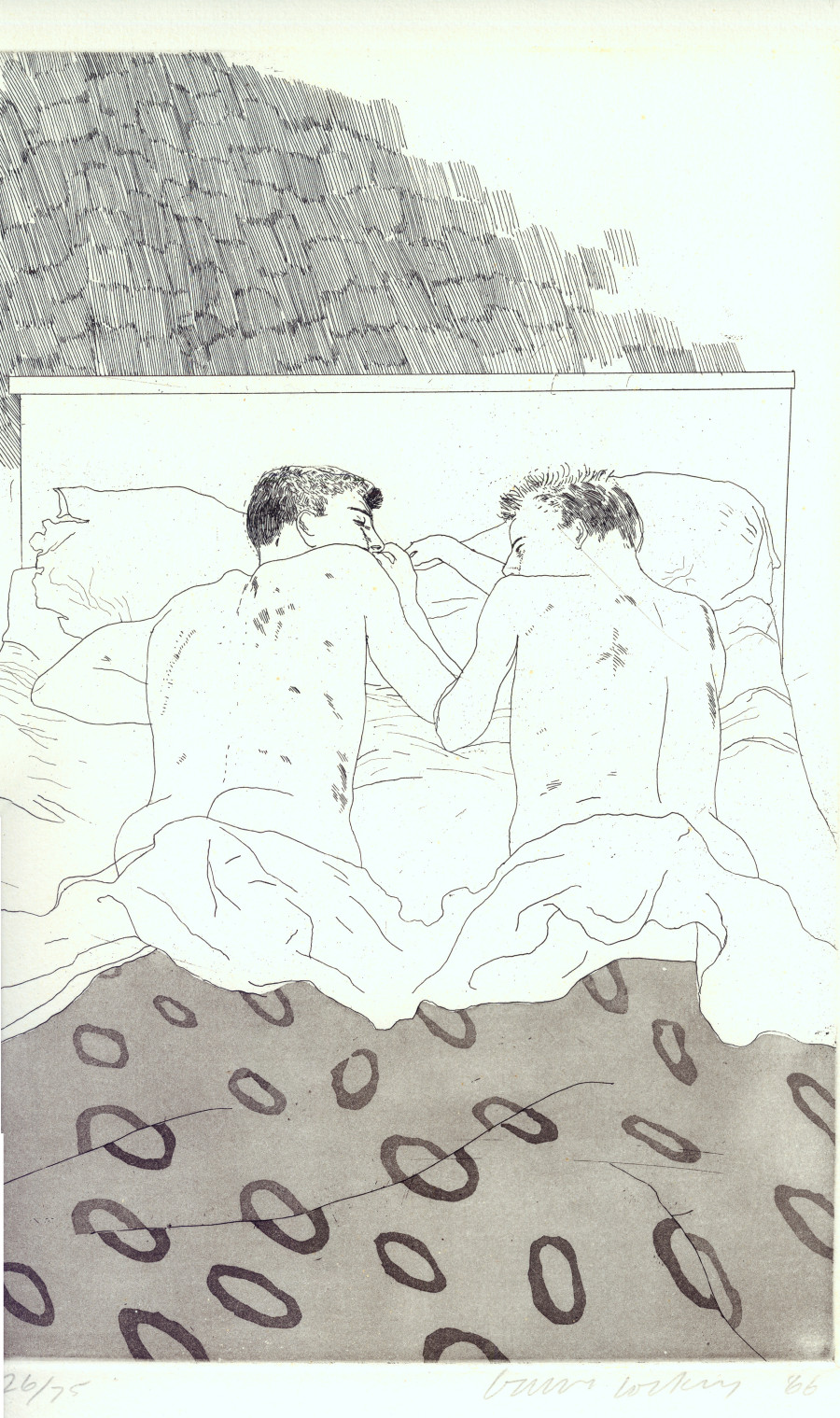

Those multiple voices have launched exhibitions like “Queer Threads: Crafting Identity and Community” (curated by John Chaich), “STROKE: From Under the Mattress to the Museum Walls” curated by Robert W. Richards, and “After Our Bodies Meet: From Resistance to Potentiality” (curated by Alexis Heller). Aside from the shows, O’Hanian’s team has built up a stunning permanent collection, one that includes pieces by the likes of David Hockney, Robert Indiana and Peter Hujar. They’ve borrowed works from the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress, and now they’re lending too. From a 60’s loft to a Wooster Street staple, Leslie-Lohman has been blossoming for over four decades.

David Hockney, Two Boys aged 23 or 24 from: Fourteen Poems from C.P. Cavafy, 1966, Etching and aquatint on wove paper, 13.75 x 8.75 in. Foundation purchase with funds provided by Ray Warman and Dan Kiser.

Still, O’Hanian sees potential for growth. “What we hope that we can do — and what we care a great deal about — is treat and deal with issues of gender and sex in a professional museum setting that is done in a straight forward and honest manner. So that other museums have the courage to do so.”

The art landscape is obviously much different than when Leslie and Lohman began collecting — in terms of sexual and gender representation and the scale of the art market. But the traditional aspects of the art world persist. “My general overarching perception of the art world is that it tends to be relatively traditional based upon the fact that it’s commerce related. With commerce comes caution.” Even in Provincetown, O’Hanian’s home before New York City, traditional landscapes reign supreme. “Stuff pops up here and there, but they’re not taking as many risks as they can.”

Berenice Abbott, Margaret Anderson, ca. 1923-26, Silver gelatin print, 13 x 10 in. Foundation purchase with funds provided by Alix L.L. Ritchie and Marty Davis.

Leslie-Lohman’s mission statement prioritizes a desire to exhibit and preserve art that speaks directly to the many aspects of the LGBTQ experience. That includes the transgender experience. “We’re definitely expounding our mission, and we definitely have a strong desire to be inclusive as we can be, involving other underrepresented communities. It’s non-heternormative core of who we are.”

“An international aspect is also very big for us,” he added.

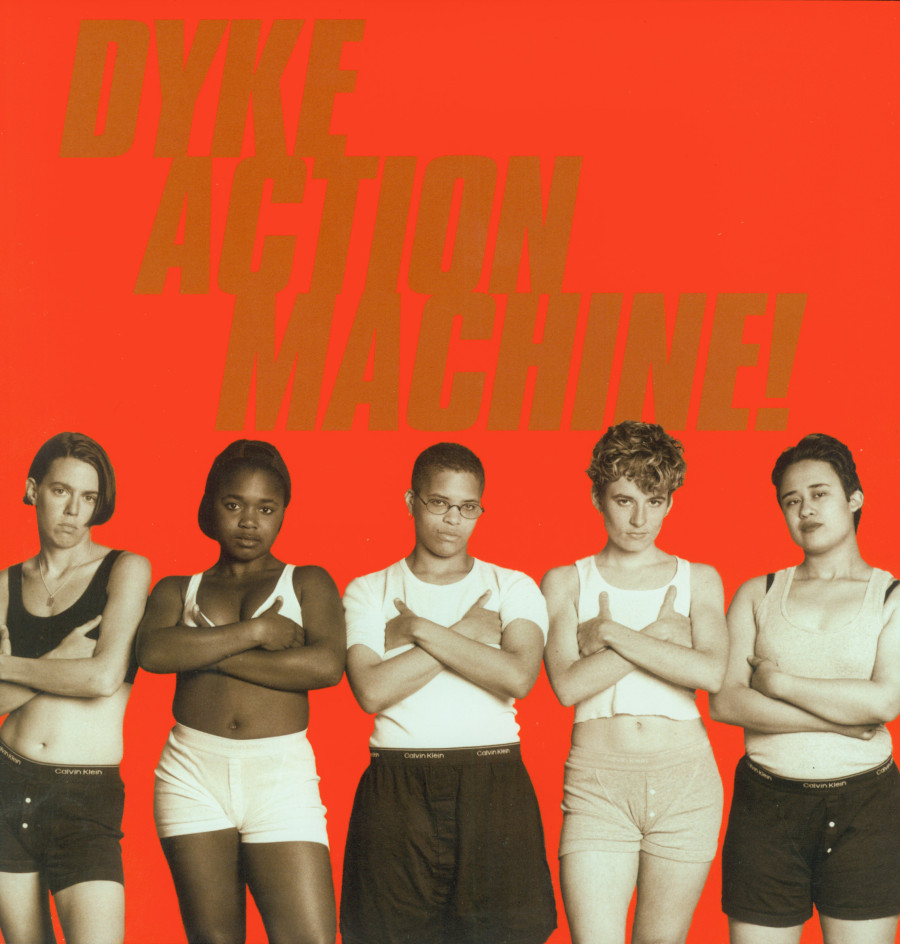

Dyke Action Machine (DAM), Do you love the dyke in your life, 1995, Processed ink on paper, 8 x 8 in. Foundation Purchase.

This month, the museum will reach another milestone of sorts. The exhibition “Classical Nudes and the Making of Queer History” will show off a piece by none other than Michelangelo Buonarroti, of “Pieta” and “David” fame. Curated by Jonathan David Katz, the collection places the nude at the center of early same-sex representation in art, reexamining the visual meaning of early queer history. For Leslie-Lohman curators, and O’Hanian, the question of what makes a work gay, whether it’s been crafted by Michelangelo or an outsider artist, never ends.

“It’s really interesting,” O’Hanian mused at the end of our interview. “On the one hand, you know a work is gay when you see it. On the other hand, we’re talking about artists and people who have just been marginalized, and they often still live within a marginalized community. At the then end of the day, what is the artist’s intent? What do they want to convey in making that particular piece of art? I am directed more, than by anything else, by wants and desires and understanding.”

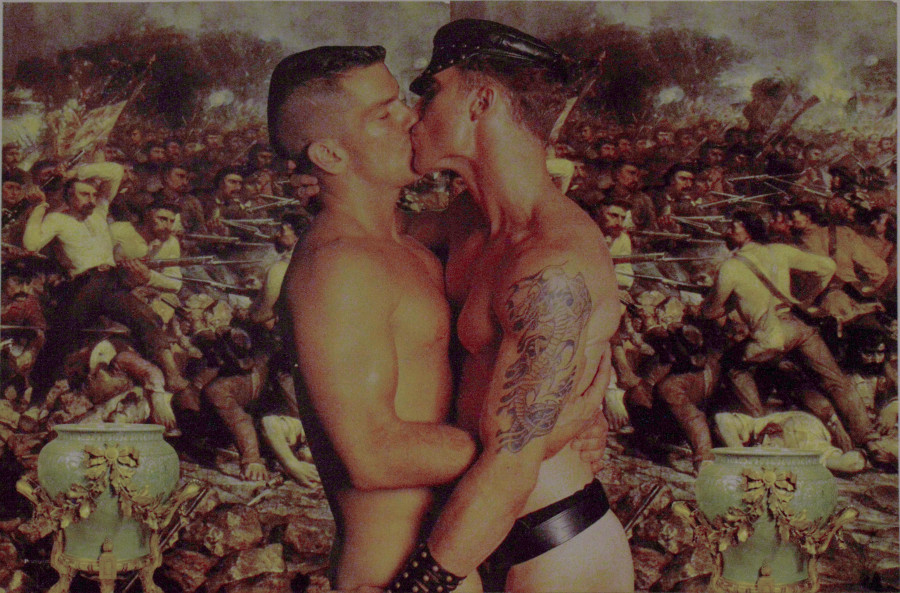

Ingo Swann, Male Love – Not War, n.d., Collage, 11 x 16.5 in. Gift of the Ingo Swann Estate.

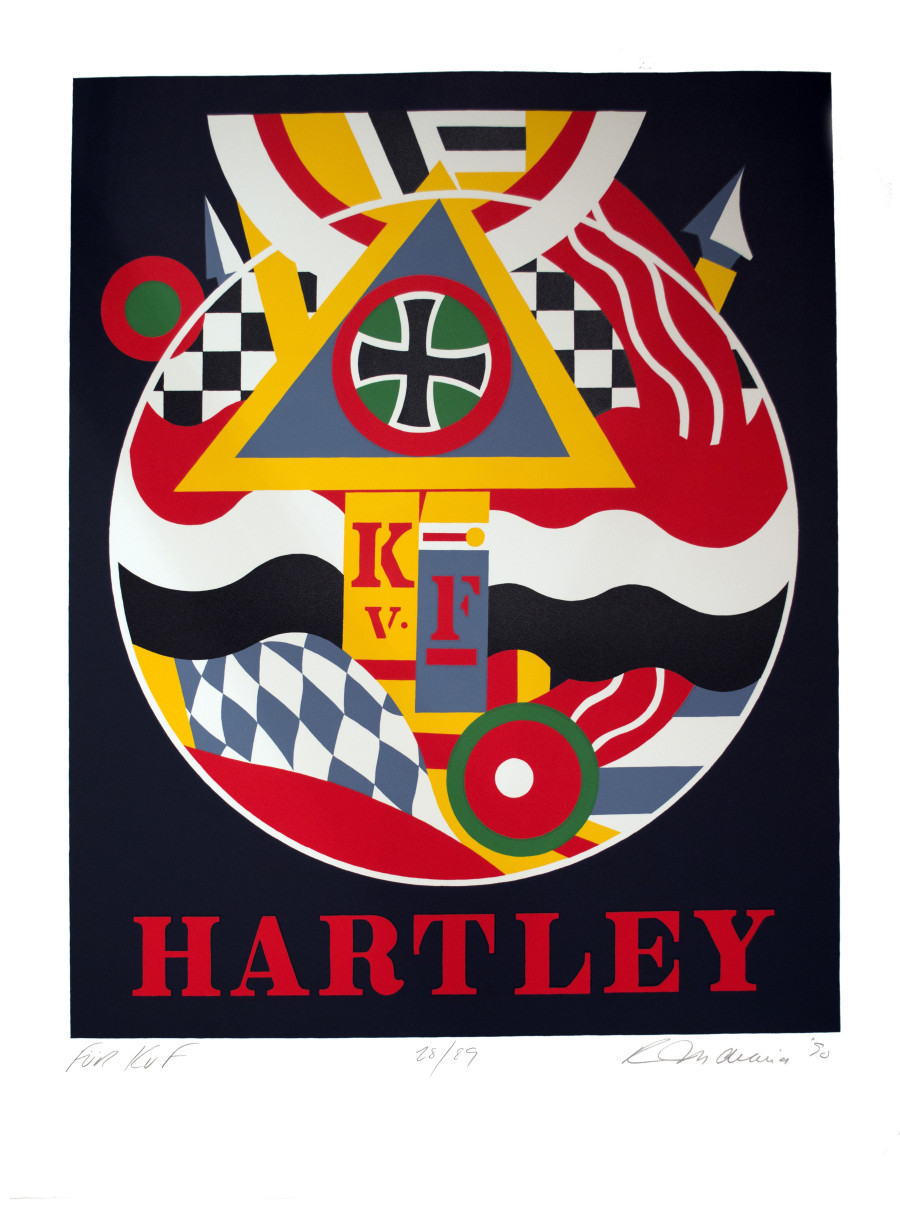

The images includes in this post depict artworks from “Permanency: Selections from the Permanent Collection.” On view starting October 18 will be “Classical Nudes and the Making of Queer History.” Stay tuned for more that exhibition to come.

Robert Indiana, FÜR K.V.F., 1990, Color screenprint on Rives BFK, 40 x 30 in. Foundation purchase with funds provided by Louis Wiley, Jr.

You Might Like