Hate Yik Yak And Anonymous Gossip Sites All You Want, But They Won't Go Away

Throughout 2014, students at Colgate University in central New York were outraged by a slew of racist comments. They didn’t know who said them, just that they came from people on or close to campus. That’s because the offensive remarks appeared on Yik Yak, an app that shares anonymous posts with those nearby.

Yik Yak, which allows users to reach other users within 1.5 miles, is the latest social media craze on college campuses, and one that can send a school into an uproar with just a few vicious posts. Students protested at Colgate in September, arguing that the racist messages circulating on Yik Yak were symptomatic of larger diversity issues at the school.

Those posts became even more hateful after students demonstrated in December in response to the deaths of unarmed black men Michael Brown and Eric Garner. Some students were singled out in the “yaks” for physical threats.

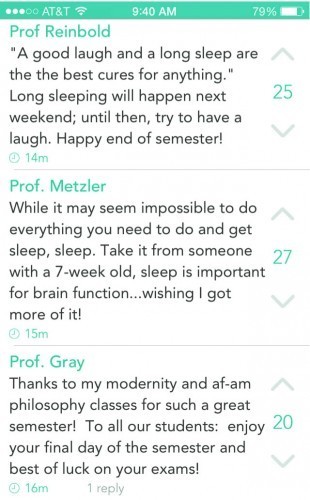

In response, some Colgate faculty members had an idea: to bombard Yik Yak with positive comments attached to their real names and clean up the local forum by example. More than 50 faculty participated during the Dec. 12 experiment. But by the next week, biology professor Geoff Holm said, the posts had returned to their usual tone.

“The posts are mainly focused on sex and poop again,” said Holm, who helped organize the “Yak Back” effort.

“It’s the Internet equivalent of the truck stop bathroom wall,” he said. “Some of the posts are amusing, some of the posts are about genitalia and bodily fluids, and some of the posts get downright racist. So how do you control that? How do you as a campus community say, ‘You can do this, but you can’t do that’ with the posts?”

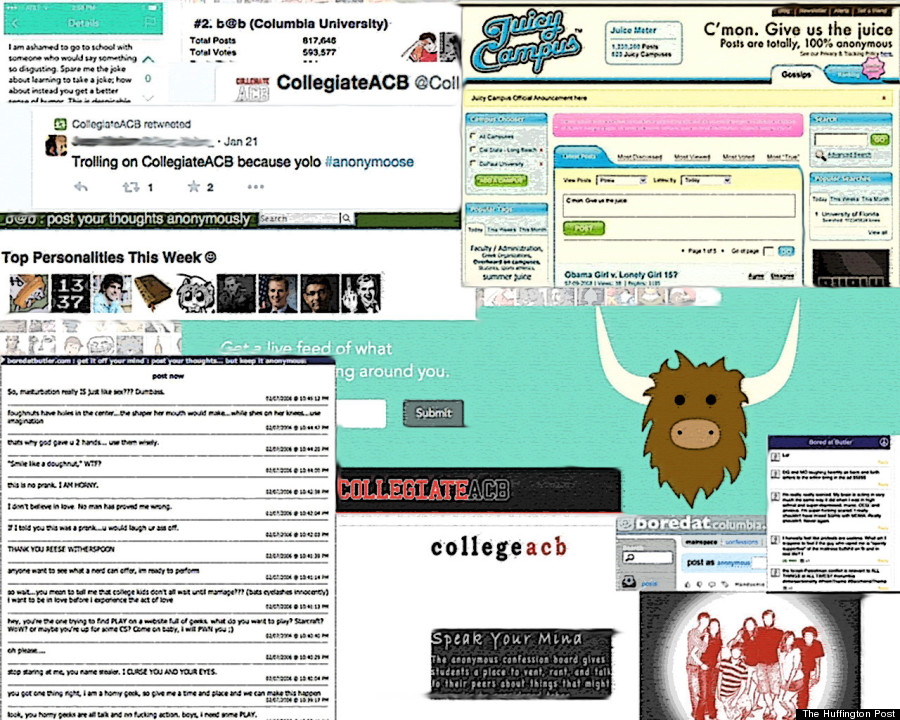

Nationwide, 2014 appeared to be the year of Yik Yak on college campuses, but the existence of anonymous online gossip sites is far from a new dilemma for universities. For the better part of a decade — since the rise of JuicyCampus in 2007 — colleges have struggled to deal with unruly, reckless and sometimes savage messages spread through anonymous Internet forums.

“I think with these forums, we’re getting a finger on a pulse of how racist many students are,” said Andrea Press, a University of Virginia sociologist who spent two years researching College ACB, a now-defunct gossip site. It’s shocking, Press said, because we’re seeing a side of people that is often kept hidden.

Princeton students protesting in December over the deaths of Brown and Garner were described on Yik Yak as “colored people getting militant.” Demonstrations at Penn State University prompted Yik Yak users to post messages like, “I hate porchmonkeys.” Already this year, students have complained of similar comments appearing at Clemson and the University of North Carolina.

Back at Colgate, students who spoke with The Huffington Post said they’d be happy to see Yik Yak banned on campus — some schools have blocked such websites and forums from their networks — but all agreed it wouldn’t do any good. After all, users could just jump to a different WiFi network to access Yik Yak.

Lawsuits don’t look like the answer either. Thanks to the federal Communications Decency Act, operators of such websites and apps are protected from liability for malicious comments that users make in their forums, just as news sites aren’t liable for their comment sections.

Yik Yak says it has filters triggered by racist, homophobic and other hate speech that can remove a post soon after it has been posted. But that clearly hasn’t stopped such messages from appearing and circulating on many campuses.

Anonymous posts can get ugly fast. At Vanderbilt University, users of Collegiate ACB, which was popular in 2012 and 2013 before shutting down, referred to a woman who reported a sexual assault at a fraternity as the “girl who ratted,” among other accusatory and often vulgar terms. Iowa State University users turned to Yik Yak to spread the word about a Snapchat account that was posting illicit photos of students on campus. At Bored@Baker, an anonymous forum confined to Dartmouth College, someone posted a “rape guide” that targeted a specific student, who later came forward to say she had been sexually assaulted.

“[Students] wonder if the people whom they pass on campus walkways are the posters of this bile, or a person in class or the dining hall,” said Alison L. Boden, Princeton University’s dean of religious life. “Yik Yak won’t stop students’ activism, their speaking out, but it leaves them feeling reviled, surveilled and unsafe.”

They Rise, They Fall

Although JuicyCampus was the first campus-based gossip forum to attract national controversy while spreading to hundreds of colleges, it wasn’t the first to exist. That was the Bored@ franchise.

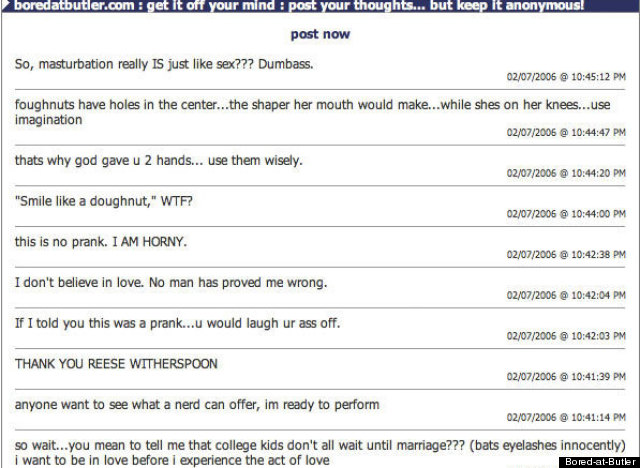

Jae Daemon — the moniker preferred by the Bored@ founder, who wishes to be anonymous himself for this story — said he launched the first iteration in January 2006 when he was, aptly, bored in the Butler Library at Columbia University. He then expanded the platform to several other selective colleges, and by March 2007, The New Yorker had deemed Daemon’s websites the “new bathroom wall.”

At the time, Twitter was in its infancy, Facebook had no feed and MySpace was all the rage. Bored@ was a place for people to “truly” speak their minds, Daemon said, and its popularity grew without promotion.

“Bored@ has survived over the years by word of mouth, curious users who find their way to it and those who have enjoyed the site enough to anonymously invite others,” he said.

While Bored@ focused on elite institutions — its college-specific forums are restricted to students with a valid email address from that school — recent Duke University graduate Matt Ivester launched his own, splashier version called JuicyCampus with a broader canvas. Ivester’s site would eventually reach 500 campuses nationwide.

“When I started it, I just thought it would be something that would be really popular,” Ivester said. “I thought it’d be kind of lighthearted and entertaining. Didn’t think too much how, when people are anonymous, it can get much more vicious than it ever would in person.”

JuicyCampus worked, Ivester said, because people could talk about campus celebrities there the same way they talked about national celebs. But, he conceded, the freedom to attack individuals as fat or anorexic or promiscuous was also its downfall.

Colleges banned the website from their servers as its negative side drew criticism from students. The attorneys general of Connecticut and New Jersey opened consumer fraud investigations into JuicyCampus. Advertisers abandoned the website over its salacious reputation.

“There was no advertising revenue, no business model that made sense,” Ivester said. “It wasn’t fun to run, and the anonymous model was hurtful, and a lot of the posts were just so mean-spirited.” He closed up shop in February 2009, for a time redirecting visitors to the page to a new player: College ACB.

Though similar to JuicyCampus, College ACB added some user regulation features. Even then, the same kind of prurient gossip prompted student boycotts of the site. It shut down in January 2011. The next year, Collegiate ACB launched to replace College ACB.

The two Collegiate ACB co-founders, University of Florida student Kirk Henf and University of Central Florida student Tim O’Shea, tried to link the site with controversy, actively seeking publicity after threats on the site led to arrests, when university police departments contacted the site about threatening posts and throughout the brouhaha over Belle Knox, the Duke University freshman whose career as a porn star sent the campus into a tizzy.

But even the outing of Knox wasn’t enough to keep the site going, and it never reached the same level of popularity as College ACB.

When Collegiate ACB was sold in mid-2014 to an undisclosed buyer on online auction site Flippa for $27,500, one co-founder wrote in Flippa’s listing, “The attention that has been associated with it as of late, although positive for business, is something that has deeply impacted relationships with friends and family, and I no longer wish to be a part of something that has this negative connotation involved.”

Yik Yak came along in late 2013, but has grown exponentially in the past year. The company, which declined repeated requests for interviews and comment, has reportedly raised some $75 million in new financing. In addition to filters for racist and homophobic words, representatives for the site point out that users can essentially censor each other by down-voting messages.

Yet Yik Yak is facing the same turmoil as its predecessors, including calls for boycotts on campus.

Why Students Go To Gossip Sites

Defenders of these anonymous forums can be hard to find amid the flood of student op-eds arguing against them. Yet there’s no doubt they have a dedicated user base.

“For me, the reason why I am drawn to the app, why I use it so much, is I enjoy making other people laugh,” said Tyler Thompson, a Stanford University sophomore. “When I get a lot of up votes on a yak, that brings me a lot of satisfaction.” Thompson is a frequent “yaker” who was approached last spring to become an ambassador for the app on campus, a paid gig where he hands out Yik Yak swag to Stanford students.

Whereas Twitter is good for tracking current events, Thompson said he mostly uses Yik Yak to see what people are talking or joking about on campus. It bothers him when people dismiss it as a cyberbullying app, he said, because “98 percent of the content is not that way.”

While in Pakistan during his winter break, Ohio Wesleyan University senior Ibrahim Urooj Saeed said he saw lots of messages from Pakistanis who study at U.S. colleges and were home visiting family. Those posts offered useful perspective on bouncing between the two countries.

“It’s very interesting to see the challenges some students face when they spend a semester on a college campus and then suddenly are in Karachi where their freedom levels are a lot lower,” Saeed said.

Rachel Drucker, a Colgate sophomore and activist with the Colgate Association of Critical Collegians, sees Yik Yak from a different perspective. As someone who she said has been on the receiving end of hatred from anonymous messages, Drucker worries that some of the same people who make the vile posts could be sitting next to her in class.

“Even if someone posts something on an anonymous forum that they might not say in public, it still speaks volumes that they would choose to post anything at all,” she said. “Oftentimes, Colgate students and faculty say that we shouldn’t worry about Yik Yak because people will post hateful things on anonymous forums that they wouldn’t ever say out loud. This is not at all comforting to me.”

The primary issue for the failed sites, however, has not been students’ comfort level but the effect of all the criticism on their profitability. Most of their income has come through advertising, so as soon as controversy-wary companies start to pull their ads, the revenue that keeps the sites afloat vanishes, too.

That’s one key distinction for the Bored@ sites: They run on donations from users — though they’re not turning a significant profit. Daemon said he works on the web forums because he loves the “technical and philosophical challenges” of building a “pseudo-anonymous environment.”

A screenshot from the early days of Bored@Butler, an anonymous forum at Columbia.

But that freedom from advertising concerns doesn’t mean Daemon can ignore the issue of hateful posts. His websites promote some users to “trustworthy personalities” with moderation privileges, and they vote on what should be done with a flagged post. Daemon suggested that an advantage of this system is that “moderators have the ability to collaborate with their peers on why one should vote a certain way.”

He said he isn’t afraid to shut down one of his sites temporarily when it becomes overrun by racist or sexist comments. He’s also happy to assist police when they spot a serious threat in a forum, like the bomb threat against Dartmouth’s commencement in 2013, which police and the FBI easily traced back to the user who posted it. Around the country, more than a dozen people were arrested in the fall 2014 semester for making similar threats on Yik Yak.

Thompson, the Stanford student, argues that Bored@’s moderator regulation is similar to Yik Yak’s down-voting feature — a few down votes and a post is gone. While he concedes that anonymity frees some users to say horrible things, he sees Yik Yak’s strength ultimately as a forum for inside jokes and commentary.

“It makes you feel part of the community,” Thompson said. “When a funny thing is actually catered to our school, our campus, it makes it that much funnier.”

The Toxic Side Of Anonymity

“The Internet has greatly expanded all speech, including good speech and so-called bad speech,” said Tracy Mitrano, former director of IT policy at Cornell University. “That is a reality colleges and universities must contend with.”

The fact that anonymous forums produce discourse so drastically different from what most people would say face to face can be explained by the “online disinhibition effect,” according to the social psychology experts. Freed of their own identity in a sense, people drop their self-restraint. They may express their feelings, including anger and bias, more intensely. The safety of anonymity also encourages risk-taking, which doesn’t necessarily bring out the best in people.

Once people decide to enter such forums, the anonymity itself can create a common identity with strong group norms, according to research by Robert E. Kraut, a professor of human-computer interaction at Carnegie Mellon University.

“I know how popular this type of content can be,” said Ivester, the JuicyCampus founder. “I think it would be fair to say I’m disappointed, but I’m not surprised that companies like this continue to pop up and operate. They exploit a human nature.”

And so the cycle seems likely to continue: The new website or app will advertise itself to college students as a place to truly speak their minds, until salacious gossip, hate speech and vitriol become its most noted aspects while the founders disavow such comments. Eventually a loss of revenue stemming from the negativity will kill the site, and a copycat will rise to replace it.

Today, JuicyCampus, College ACB and Collegiate ACB are virtually unknown to undergraduates, while Bored@ remains limited to a handful of campuses. Ivester still owns the URL JuicyCampus.com, which now leads to one of his latest apps: Kindr, which directs users to send compliments to people or read uplifting news. He recently launched Reveal, a social media app that requires users to send photos with their comments, which he argues is an push against anonymity.

Yik Yak remains the hot app on campus, even as competitors are already vying to replace it. DormChat users can anonymously message each other on campus. People with an .edu email can sign up for erodr; while Secret, which is basically a Yik Yak geared toward working adults.

Colgate professors say they’re still keeping an eye on Yik Yak. If the yaks focused on their college community turn really vile again, Holm said that he and his colleagues will likely jump back in to remind students that they’re watching and that words have consequences.

You Might Like