Each generation of gay men has the distinct experience of being uniquely impacted by HIV. One of the best-understood and often explored generational experiences of HIV is the early years — a time when the disease violently and unexpectedly emerged in the community. For those of us who come of age after those events, HIV didn’t arrive to alter the world, as we knew it. It was the world, as we knew it. For our entire experience, HIV has been incidental to our lives.

The AIDS generation endured unimaginable horrors. I still marvel that they kept our culture and community alive through those war years. That really is the only way I can think to describe it- war years. Many, many lives were lost, incalculable pain was endured, and the injustices of the world were magnified. But the war wasn’t won it was simply transformed.

I am part of the gay post-war generations. Only this wasn’t the post war years of GI Bills, swimming pools, and shiny new cars. It was more like post war East Berlin — a world of guard towers, barbed wire, and machine guns. These were our cold war years living under the specter of a totalitarian regime and fearing death, not from secret police or nuclear annihilation, but from a raging epidemic. That was our daily life. It was less a life of resistance and more one of co-existence.

Growing up, I knew fear all too well. When I was 12 I saw one of the first TV movies about gay men and AIDS, As Is. I attentively watched the gay men in the film and while I didn’t call myself gay then, I knew that I liked other boys and that this story was about me. In a pivotal scene, one man discovers a KS lesion on the back of his lover and they realized the impending horror. Immediately, I went to the bathroom to frantically examine my back for KS. I hadn’t even has sex yet but I understood a very simple fact. I was like those men and AIDS is what happens to those men, to men like me.

Coming of age in the midst of the epidemic meant that HIV was a constant in our lives and continues to be for the generations that came after me. For many of us, then and now, HIV isn’t a mater of if but a matter of when. HIV seems more like modern gay male conscription.

The HIV generations never had the benefit of cultivating a sexuality or sexual identity in the absence of a killer disease. It’s a necessity of the human spirit to be free, to explore, and to express your sexuality. As young gay men, we never got that opportunity because death and disease was around every corner, as well as fear, shame and guilt.

We were bequeathed “safe sex” by a well-meaning older generation. It became our catechism and we had to make sense of the fact that our sex wasn’t just dirty and immoral but it could kill us. We inherited a world of AIDS activism while some of us also perceived that a strong case was never really made for the value of the lives of gay men, in particular gay men of color. It was easier to gain resources and funding by talking about the “innocent victims,” such as housewives and little boys. Saving gay men was a secondary, less talked about benefit, even though we were, and continue to be, the majority of all infections.

These dynamics and the conditions of the epidemic doomed us to intergenerational discord. When I tested positive as a young queer man in 1998 I was called, “irresponsible,” “stupid,” “disrespectful of those who came before,” and even a charge that’s ubiquitous today – “complacent.”

Young gay men are not complacent. Complacency is not driving the epidemic. For the post-AIDS generations, HIV is a constant in our lives and it’s never far when we are having sex, or looking for sex, or thinking about sex. We have different relationships to the epidemic compared to those who came before. And for young gay men today, their world may look different, their choices around sex, condoms and PrEP may look different, and their activism may look different. But it’s a profound misunderstanding of the experience of young gay men to call it complacency.

Misunderstandings are common between the generations. The problem is that over the past 30 years, we haven’t had great relationships between the generations. Perhaps one of the more poignant losses of the epidemic is the loss of a relationship between the generations.

When I was coming of age there was no one there to mentor me or my contemporaries. Potential mentors were either dead or were, understandably, too traumatized to offer mentorship. Gay men my age relied on our peers or ourselves. And as luck would have it, we were the perfect generation to take care of it on our own — we were latchkey kids. In our minds, we already had the skills to make our way in the world. So we did the best we could and many of those intergenerational relationships went uncultivated.

Sadly, my generation only repeated this cycle when the next generation came along. We didn’t have mentors, we’d done it ourselves, so why or how would we mentor those who came after us? The era of disconnection persisted.

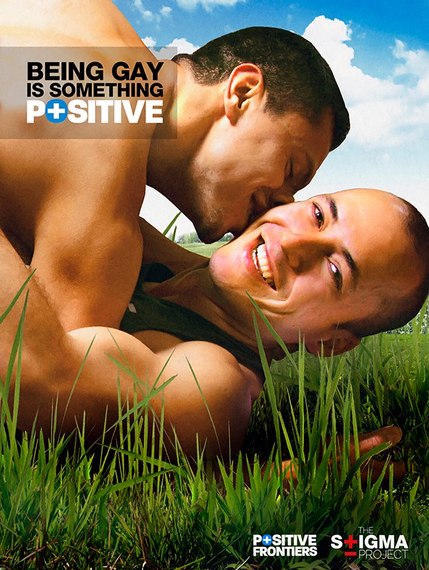

But the cycle can be broken and the bridges can be repaired. We can’t bring back the dead or turn back time but together we can determine the course of our community. We can choose to invest in reciprocal intergenerational relationships. We can reconcile our different relationships to the epidemic and foster a community that prioritizes empowerment, self-determination, and resiliency over stigma, fear and condemnation.

So whether it’s gay pride month, or World AIDS Day, or just an average Thursday, we can decide that we are going to commit to building relationships, improving communication and strengthening communities between the generations. In the past thirty years we’ve accomplished so much. Investing in this endeavor could be one of our greatest and lasting achievements.

You Might Like