AIDS Nostalgia and 1991's <i>Someone Else From Queens Is Queer</i>

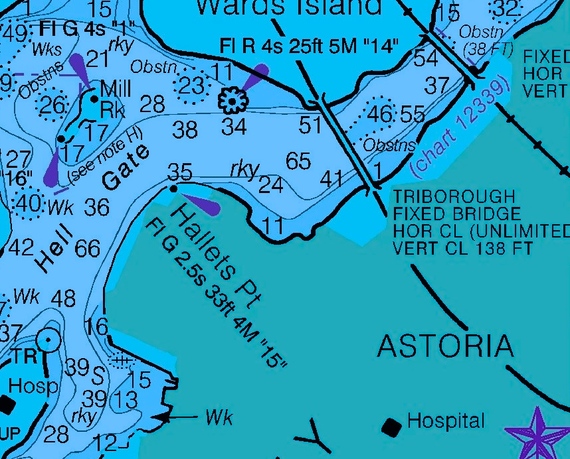

I have steered my small craft of attention carefully away from most of the fire-engine-red buoys of so-called “AIDS nostalgia” that have appeared in the last few years and reveal, like freshly marked symbols on the newest, most accurate maps of busy waterways, significant shifts in depth and current.

Most recently I nodded at friends and clients, gay men all, who described their visceral responses to Ryan Murphy’s HBO adaptation of Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart. I didn’t watch it, as I had also allowed myself to drift past that drama’s Broadway revival without stopping by as though it were a once-familiar port of call. I similarly avoided several other cultural markers of our acknowledging the AIDS crisis as a landmark that now appears far behind us, upriver, as we slowly ease toward the further reaches of middle age and the inevitable delta that lies ahead.

Detail, Office of Coast Survey Nautical Chart, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce

Frankly, it’s just too painful for me. Coming to New York City in 1989 after college, I narrowly missed being part of the generation of gay men and their loyal, loving female friends who found themselves squarely in the spinning eye of that shockingly sudden and destructive squall that decimated entire friendship networks. But “I was there,” as Sondheim says.

At the time, it must have seemed to them like an endless antediluvian affliction as, Noah-like, they looked up at the sky and thought, “More? Really?” Yet now, in hindsight, even with the mostly private anxieties and warnings of seroconversion still a prominent internal map of our protogay intimacies, the high-water marks of those years telescope away from us as we revisit these ships’ logs of our journeys from the those days.

I’m sorry to make so much of the nautical metaphors, but they’re poignant for me, revealing some core, atavistic tenderness within my heart, like those speeches of Shakespearean shipwrecks that wreak their dislocating havoc just before the curtain rises and are already presented in poetic images by the drenched, dazed, and — hello — marooned survivors in Act One, Scene One.

But I’ve marked the passing and the remaining of my own private AIDS crisis in quieter, more domestic and less publicly shared ways. It’s a jealous, covetous sort of mourning ritual: “Mine. Mine.“

For example, I retain, like a blurring tattoo under my clothing, the final image of The Destiny of Me, Mr. Kramer’s followup to the shocking cri de coeur of The Normal Heart: that of actor John Cameron Mitchell’s stricken young face as his character catches a glimpse of his future as a gay man who will find himself swept up in something far, far beyond his reckoning.

Of course, the cauterizing scars of the wickedest, white-hot edges of the zeitgeist are experienced by us all in intense solipsism. Somehow, by taking a pass on the collective enactment of our remembrances, I am attempting to defy and disgrace the process of coming to terms. I don’t want to heal from these wounds. I demand that they remain fresh and flowing. But, of course, they inevitably grow less-vivid, cooler, both the memories and my righteous rage, for better and for worse.

Still, I hold rather desperately — and I mean this — to my personal totems like — sorry — a sailor who lashes himself to the mast during a tempest and finds himself ridiculously still strapped there and stuck the sunny morning after.

And I honestly don’t know the extent to which this protectively intended bondage to the past continues as my own self-scarring replay of old trauma or in venal, desperate or perhaps transcending servitude to wraiths dead or alive.

Of course, it would be nice to spy an albatross like in Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, that symbol of the spirit’s liberating ability to survive our wreckage and soar through the sky or drop onto solid terra firma, even if only in the form of a perch on an old pylon of the rotting West Side piers on the Hudson.

But, for me, without question, it’s in written works of creative expression — those artifacts of a community’s presence and processionals as real as a “rent past-due” slip under the door — that I find my solace and my North Star, helping me steer a course forward. In terms of AIDS and among living authors, that’s works like Mark Doty’s collection of poems My Alexandria; or the still-quickening poems of friend-poets like Steven Cordova, David Groff, and Scott Hightower; or indispensable essays like Samuel R. Delaney’s razor-sharp and unapologetically carnal “Times Square Red, Times Square Blue”; or Christopher Bram’s tender and carefully wise take on the AIDS generation’s gay-male belles lettres in his enlivening Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America.

As Bram astutely reminds us, the theater is a particularly vital and quickly responsive venue for depictions of recent and local autos de fé and high-wire escape acts. Tony Kushner’s Angels in America echoes with Kramer’s historical dramas, and each of those with other works, like Paul Rudnick’s generously romantic Jeffrey and that miracle of theatrical invention and heart, Jeff Weiss’ Hot Keys. I include in my personal mememto mori of those times another particularly special performance text.

I never saw a performance of Someone Else From Queens Is Queer, the 1991 solo show of AIDS activist and health policy enfant terrible Richard Elovich, but know it from the text published in the journal Theatre in the summer 1993 issue, which I’ve always kept a copy of and read every few years, like I do with To Kill a Mockingbird.

I worked with Elovich at Gay Men’s Health Crisis in the mid-’90s, when he was one of the sui generis geniuses of AIDS prevention and the integration of life-saving harm reduction models to HIV. (He now holds a Ph.D. in medical sociology from Columbia University.) Back in the day I was intimidated and thrilled by his kinetic passion and sense of mission.

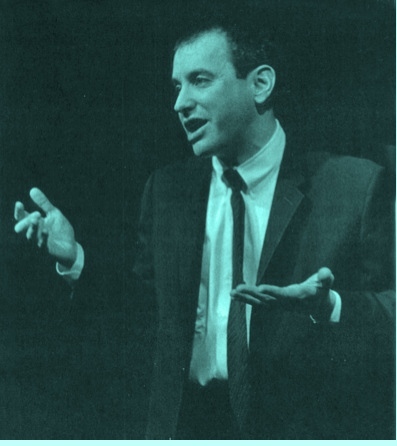

Photo of Richard Elovich in Someone Else From Queens Is Queer by Dona McAdams, courtesy of Theatre

You can feel that wonderful life force just reading Someone Else From Queens Is Queer, an intellectually giddy mash note to the ACT-UP boys and treatment activists in leather jackets who sprang fully formed as if from the head of a Tom of Finland-drawn Zeus in response to the torpor of government response to the AIDS Crisis.

Gregg Bordowitz (to whom Someone Else From Queens Is Queer is dedicated), Charles Brack, Javid Syed, James Learned, Peter Staley, Spencer Cox, John Hatchett, Mark Harrington, Stephen Gendin, David Barr, Dave Nimmons, Gregg Gonsalves, Derek Hodel, Derek Link, Michael T. Isbell, and Thomas K. Duane (and those indefatigable and poised women who labored in the same trenches, like Denise Drayton, Petra Barrios, Laura Morrison, Michelle Lopez, Kim Watson, Barbara Hughes, Barbara Warren, Christine C. Quinn, Karin Timour, and Joy Episalla) — amongst many, many others, these are my personal local heroes and heroines..

These were the mostly lily-white, mostly male, mostly suburban-raised and staunchly middle- and upper-middle-class sissy superstars of righteous rage, drunk with grief and power, bitch-slapping Reagan-era bureaucrats with their audacity and desperation, and Elovich’s text sings soaring and cracked elegiac arias for them from some East 10th Street tenement window’s fire escape at 3 a.m.

Here’s my favorite part, which starts out comparing television sitcom families The Munsters and The Addams Family as if each exemplified a different class-based ethos of Jewish-immigrant assimilation in America, in a breathless, sexy, and silly argot instantly recognizable to those of us who shared those supercharged, heady days, and which formed some of the formative ideological and intellectual underpinnings of AIDS activism:

I open the door and we go in. We sit on the couch. I put my hand- “Now on the other hand you have the Munsters. Herman and Lily Munster come from an entirely different class. They are like us, from Queens. Herman Munster is different from Gomez Addams. Herman is constantly seeking to assimilate. The happiest I have ever seen Herman is in the episode where he has won, in a TV contest, a month’s free membership in the Mockingbird Heights Country Club! So he and Lily go to this country club and totally fuck up! Misunderstand everything!” -Gordie’s taking his clothes off.- “See, no matter what Herman Munster does, no matter how much he tries to sound like ‘Father Knows Best,’ he has that nose! That face! He always looks Frankenstein!” –I run for the pillows and the sheets.- “The difference is Gomez Addams can pass, and that’s all the more interesting because he doesn’t know he’s passing.” -1 turn out the light.-“The Jewish dream vision of aristocracy:” -We get into bed.-“Not ever remembering a time when one wasn’t aristocracy!”We’re both looking up at the ceiling. I’m wondering if he’s ever gonna stop! I go to put my hand.- “So later in the same show, Herman is deeply invested in this contest he has entered-he goes to the TV.” -1 take my hand back.- “Now this is a great moment of television: T V is watching TV. Herman goes to the TV and they’re announcing the contest winners. ‘The first prize is yadda yadda,’ and it doesn’t go to Herman. ‘The second prize is yadda yadda,’ and it doesn’t go to Herman. After he doesn’t get the third prize, Herman starts yelling back at the TV: ‘Why dontja tell everybody that he’s the nephew of the station manager-it’s all a fix, it’s all been fixed, fixed fixed fixed fixed fixed fixed fixed fixed fixed!’ Herman starts pounding on the TV, screaming: ‘It’s a sham! It’s a sham!’ “So here’s this image of a Jewishman on a television show, Frankenstein, screaming back at the TV doing this yiddle yiddle yimmy dance around it, wrecking it, because it doesn’t recognize him!” -1 pull Gordie’s legs out from underneath him! He falls onto his back and I kiss him for the first time. Once he stopped talking he turned into an incredible lover.

Elovich presents such a highly personal, idiosyncratic and lushly romantic portrayal of these relationships in a gloriously proud Jewish cultural frame, enacting the rolling, off-tempo lilt of that terrifying era’s special cadences, plunked out of tragic keys as it is for each generation and uniting mind and heart, loss and birth. And here it all is in microcosm, unmediated by metaphor, near the piece’s conclusion:

When Gordie’s speeches were gone, when he was having trouble just getting out what he wanted to tell the doctor, and all that was left were his dark eyes darting back and forth he kept trying to start something but he’d lose track. That’s what made him angry all the time. Losing track. He was angry with me, he was furious with me, for seeing him like that.

Twenty-three years ago this summer, those words emanating from the mouth of one of us, one of our tribe — amongst whom I worked and screwed and bitched and had my heart broken — filled me then with an aching love, and it still does.

Christopher Murray, LCSW-R, is a psychotherapist in private practice in Manhattan and can be reached via christophermurray.org.