26th World AIDS Day: Get in There, Do Something, Change Things

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and treatment as prevention (TasP) have successfully returned sexual health to the national and international headlines. Not since the early years of the HIV epidemic has there been so much constructive dialogue, progress, and involvement by the public.

Long-term survivors, HIV organizations, scientists, public-health experts, and the generation that never knew a world without HIV joined hands on the 26th World AIDS Day in an effort to educate and advocate in commemoration of those we have lost to HIV and the people living with the infection today.

While a few still wage a lonely and wasteful fight against science and progress itself, it is time to acknowledge that we finally have the opportunity to move on from a monotonous, one-way conversation and use these new tools as catalysts for serious and much-needed change.

While a few still wage a lonely and wasteful fight against science and progress itself, it is time to acknowledge that we finally have the opportunity to move on from a monotonous, one-way conversation and use these new tools as catalysts for serious and much-needed change.

Of course, it doesn’t help when one of our favorite Star Trek actors throws all logic overboard and simply dismisses today’s generation as lazy, complacent and irresponsible, but it certainly shows that we haven’t progressed much since President Reagan’s infamous call to abstinence 27 years ago.

Six of the estimated 39 million people we lost worldwide to HIV were my friends and mentors. All six would have agreed with Meryl Streep’s Margaret Thatcher when she says in The Iron Lady, [I]f something’s wrong, they shouldn’t just whine about it. They should get in there and do something about it. Change things.”

In the 1980s we did just that, and today’s generation follows suit. We too get in there, do something, and change things. My next two weeks, for example, are tightly scheduled, with 10 PrEP panels across the U.S. Yesterday I was in Palm Springs and Los Angeles, today I am in New York City at Columbia University, on Dec. 4 I will be in Cleveland, on Dec. 6 I will be in Grand Rapids, on Dec. 7 I will be in Lansing, on Dec. 8 I will be in Detroit, on Dec. 10 I will be in St. Louis, on Dec. 11 I will be in Atlanta, and on Dec. 12 I will be in San Francisco.

In the 1980s we did just that, and today’s generation follows suit. We too get in there, do something, and change things. My next two weeks, for example, are tightly scheduled, with 10 PrEP panels across the U.S. Yesterday I was in Palm Springs and Los Angeles, today I am in New York City at Columbia University, on Dec. 4 I will be in Cleveland, on Dec. 6 I will be in Grand Rapids, on Dec. 7 I will be in Lansing, on Dec. 8 I will be in Detroit, on Dec. 10 I will be in St. Louis, on Dec. 11 I will be in Atlanta, and on Dec. 12 I will be in San Francisco.

Here are five key focus points that I believe we must act on:

Sexual-Health Education and Health Programs in Schools

Sexual-health education, especially in the U.S., is a mess. In a country where religious morals often dictate the code of conduct, preparing the next generation for when they first turn wet dreams into reality becomes challenging. This difficulty manifests itself in the U.S.’s shocking teenage-pregnancy rates, which surpass those of other Western countries by 20 points, and the rising rates of new HIV infections in young people. What we need is a federal minimum requirement for sexual-health curricula that includes a judgment-free approach to LGBTQ rights, issues, and history, as well as a public youth-health program to provide vaccinations, health screenings, and counseling to all adolescents free of charge.

Decriminalization of HIV

Exposing someone to HIV with or without a condom is a crime in many places, often regardless of whether an actual transmission occurred. While this may seem well-intended on first glance, these laws heavily discriminate against people living with HIV and automatically make them culprits.

Exposing someone to HIV with or without a condom is a crime in many places, often regardless of whether an actual transmission occurred. While this may seem well-intended on first glance, these laws heavily discriminate against people living with HIV and automatically make them culprits.

Regardless of HIV status, the stigma around HIV has impacted us all culturally and emotionally. Decriminalizing HIV means alleviating that stigma, empowering, and educating.

Reclassification of HIV as a Chronic Infection

Thanks to the great strides we have made when it comes to the treatment of HIV, an infection with the virus no longer automatically equals an inevitable progression into the terminal illness known as AIDS.

Diabetes, for example, is classified as a chronic illness. Reclassifying HIV as a chronic infection instead of as a terminal illness would lead to easier access to medication, care, and services, which in turn would lead to higher rates of viral suppression and thus reduce the number of new HIV infections.

Updating of Testing Guidelines

Our prevention toolbox primarily consists of condoms, PrEP, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), TasP and testing. However, how well testing can reduce transmission risks depends on what test is being used and at what frequency.

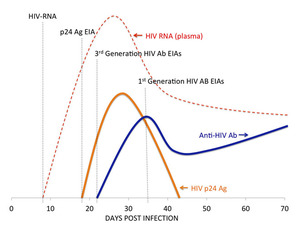

After exposure, it takes about 10 days for the virus to replicate itself enough within the body to be infectious. This is known as the “eclipse period.” The following 90 days, the “acute infection period,” are the most infectious. Currently the CDC recommends annual testing and notes that there could be some benefit from more frequent testing.

The best tests we have available today are HIV RNA tests that detect the virus seven to 10 days after exposure, and fourth-generation antibody or p24 antigen tests that detect the virus about 17 days after exposure. The time from exposure to detection is called the “window period.” In comparison with these newer tests, the first and second generations of HIV antibody tests generally have a window period of about five to 12 weeks.

The best tests we have available today are HIV RNA tests that detect the virus seven to 10 days after exposure, and fourth-generation antibody or p24 antigen tests that detect the virus about 17 days after exposure. The time from exposure to detection is called the “window period.” In comparison with these newer tests, the first and second generations of HIV antibody tests generally have a window period of about five to 12 weeks.

Testing can be costly, though, and as first- and second-generation HIV antibody tests are still FDA-approved in the U.S., they remain the most commonly used.

Updated testing guidelines should recommend that sexually active people get quarterly health screenings for all STIs, and that older tests be removed in order to shorten the possible transmission cycle of acute infections.

Access and Health Insurance

The Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act was undeniably one of the most important steps to reduce the number of new infections, by enabling people in heavily affected populations to access care. Sadly, 10 states that report some of the highest HIV-infection rates are among the 19 states that are not expanding Medicaid.

Making health insurance accessible and understandable should be a key focus.

Employees should be health-insured from the first day on the job. The current 90-day insurance gap is a vital threat to drug adherence, continuous care, and continuous prevention.

HIV medications that are currently classified as “specialty drugs” should be considered maintenance drugs and be placed in lower copay tiers.

Truvada and drugs that may be approved in the future for use as PrEP should be considered preventative medications, because that’s really what they are in this case. This would greatly decrease access disparities and increase awareness, especially on the side of the PCPs.

Drug formularies need to be easier to understand. For many people in the U.S., this is a completely new concept, and they are overwhelmed by information that is unnecessarily complicated. California Senate Bill 1052 is focused around this issue and was just signed into law in September 2014.

You Might Like