10 Children's Books That Paved The Way For A New Queer Protagonist

In Kendrick Daye and Myles E. Johnson’s Large Fears, Jeremiah Nebula may not be a bullfrog. But he is the queer, black protagonist of a children’s picture book — a genre traditionally dominated by heterosexual, cisgender, white characters. Although the politics of representation is an issue for all literary forms, parent sensitivity has made materials for young readers particularly resistant to plots that question gender, sexuality or the institution of the family.

Daye and Johnson were frustrated with those age-old patterns, so they decided to create new ones. Their recent Kickstarter campaign casts the project as both subtle and radical. Jeremiah, they say coyly, is just a boy who loves pink. But they also stress how his queer, black identity makes him “a character that defies gender roles, race politics, sexuality, and his fears.”

Jeremiah’s story builds on over 30 years of children’s books that portray LGBTQ characters, translating complex issues of gender and sexuality to an accessible, picture-heavy format. These books, though, reveal far more than cutesy anecdotes. They are instructional, cathartic, and ethical, explaining different family models, connecting children with LGBTQ identities or parents to fictional counterparts, and teaching values of acceptance at impressionable ages.

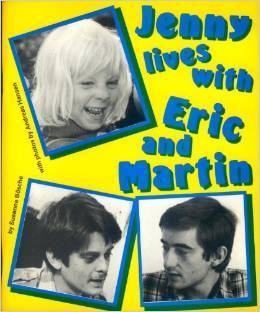

Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin by Susanne Bösche (1981)

This black-and-white Danish photobook was arguably the first to feature gay characters. Two men raise their daughter, Jenny, whose biological mother lives nearby and visits from time to time. Most events are normal children’s books fare like laundry-folding and surprise birthday parties. But the characters also deal with a homophobic comment from a stranger in the street.

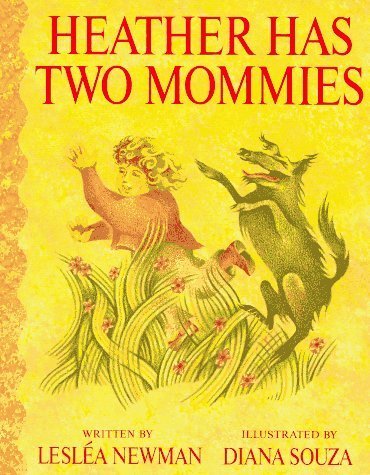

Heather Has Two Mommies by Lesléa Newman and Diana Souza (1989)

Like Bösche’s story, this one follows a child with same-sex parents. New plot points include artificial insemination and an inclusive discussion at Heather’s playgroup about different family structures. In real-life playgroups, the response to this book was far less benign: the story rocked the U.S., and the resulting controversy led to extensive parodies including a “Simpsons” version: “Bart Has Two Mommies.”

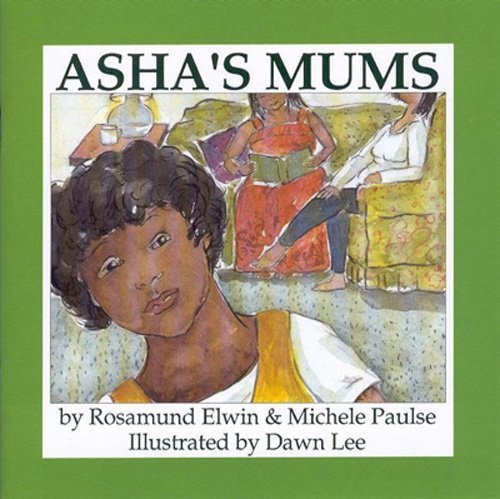

Asha’s Mums by Rosamund Elwin, Michele Paulse and Dawn Lee (1990)

Asha needs to get a permission slip signed by her mother, but she is perplexed when she must decide which of her two moms to ask. While Heather was lucky enough to have an accepting playgroup, Asha confronts a far less hospitable school — and world. It’s a tale for anyone whose family does not fit into educational bureaucracy, and Asha’s African-Canadian identity marks a decisive step away from lily-white characters.

Daddy’s Roommate by Michael Willhoite (1991)

You might recognize the name from the 2008 presidential campaign when it “came out” that Sarah Palin, back in her 1995 councilwoman days, had said the book should not be permitted in public libraries. Why? There’s a gay relationship between the the father and his new roommate-actually-boyfriend, Frank. Plus it all starts off with a divorce and arrives at a pretty clear message: “Being gay is just one more kind of love.”

King & King by Linda De Haan and Stern Nijland (2002)

Originally published in Dutch, this book offered both a new take on the royal marriage story, with a gay child rather than just gay parents. “I’ve never cared much for princesses,” says the princely protagonist, as he finds a series of potential wives paraded in front of him by his wedding-hungry mother. Then, he spots one of the princesses’ brothers. They are soon crowned King and King, and the story ends with a subversive same-sex kiss — which launched a series of conservative campaigns to ban the book.

One Dad, Two Dads, Brown Dad, Blue Dads by Johnny Valentine and Melody Sarecky (2004)

Instead of focusing on a single storyline, the book features two kids comparing different paternal figures. “Blue,” it turns out, is a not-so-subtle euphemism for “gay,” and the children slowly come to the realization that all skin-colors and sexual identities are equally valid. (Bonus points for the enchanting Seussical rhyming scheme.)

And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson, Peter Parnell and Henry Cole (2005)

A tale of two male penguins who are chick-less until a zookeeper helps them adopt Tango from a heterosexual couple. Animals are always one of the easier ways to discuss unconventional storylines, but that didn’t stop Singapore from banning the book along with two others last year. In fact, it’s ranked third on ALA’s list of “Most challenged books of the 21st century,” which is hard to explain considering how heartwarming these polar birds are. Did we mention it’s based on real gay penguins at the Central Park Zoo?

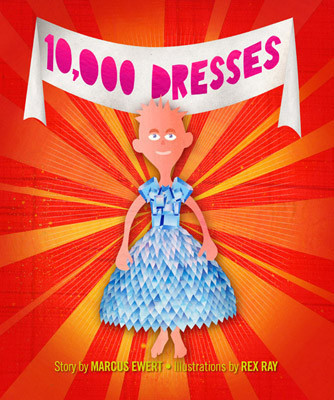

10,000 Dresses by Marcus Ewert and Rex Ray (2008)

Bailey is a boy by day who, at night, dreams of cross-dressing. His night-time escapades are rebuked by his family, until he finds a seamstress in playmate Laurel. Bailey’s story is an early forerunner to Jeremiah’s, for it broke from the gay-character plot to examine what it meant to be a gender-queer child.

My New Mommy by Lilly Mossiano and Sage Mossiano (2012)

Who says transgender identity can’t be explained to young children? Four-year-old Violet has a transitioning father who carefully walks her — and us — through the process. Like Daye and Johnson, Mossiano was frustrated with the lack of children’s materials, so she took matters into her own hands. She challenged herself to make the content accessible to a young audience, but the real challenge is the one she posed to traditional portrayals of gender in children’s books.

Call Me Tree by Maya Christina Gonzalez (2014)

The third in a trilogy that opted for gender neutral pronouns, providing what the writer called a “much needed break from the constant boy-girl assumptions and requirements.” Gonzalez took another decisive step away from the “gay parent” trend and gave us an unambiguously ambiguous gender-queer character. Her engagement with the Chicano identity also departed from the classic whiteness of LGBTQ children’s characters.

Morris Micklewhite and the Tangerine Dress by Christine Baldacchino and Isabelle Malenfant (2014)

Like Bailey, Morris has a penchant for gender-queer behavior. He loves to wear the title’s orange garment but his fashion choices leave him open to relentless teasing from his classmates. Tensions escalate, and Morris becomes physically ill from the psychological pain. Though his imagination helps him triumph in the end, the book’s real triumph is that it gives a harsh and realistic account of queer bullying.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

You Might Like